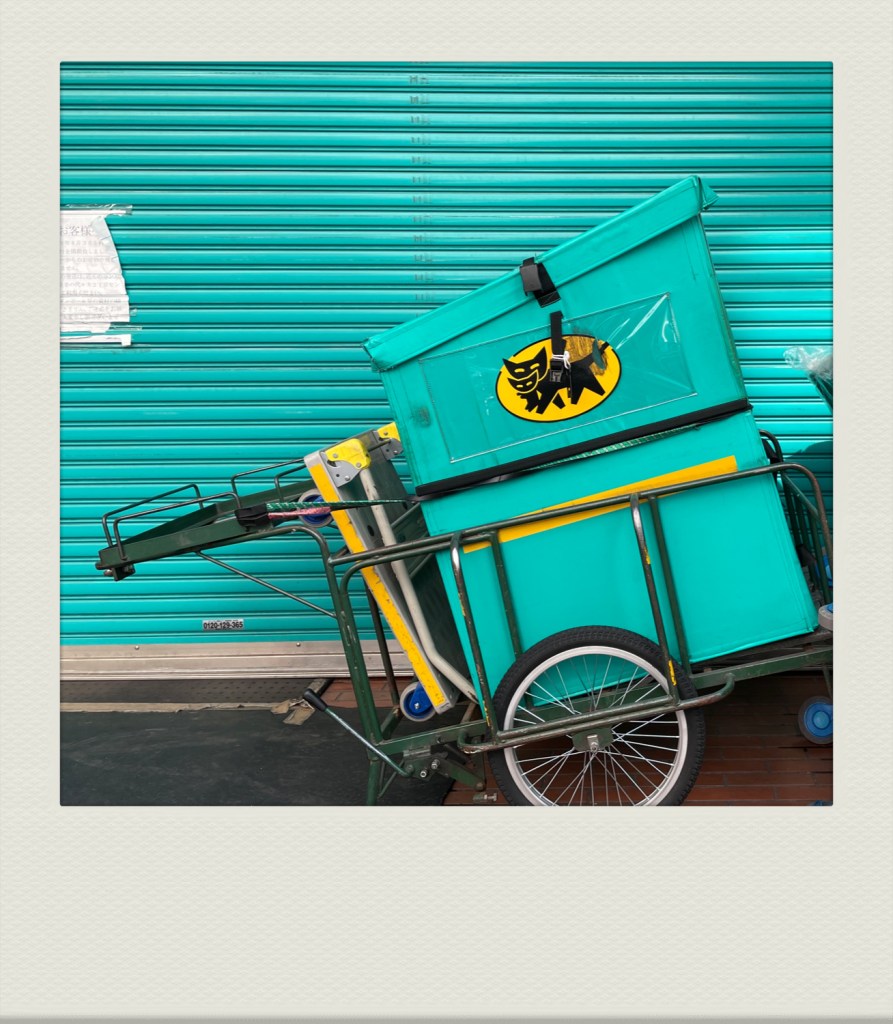

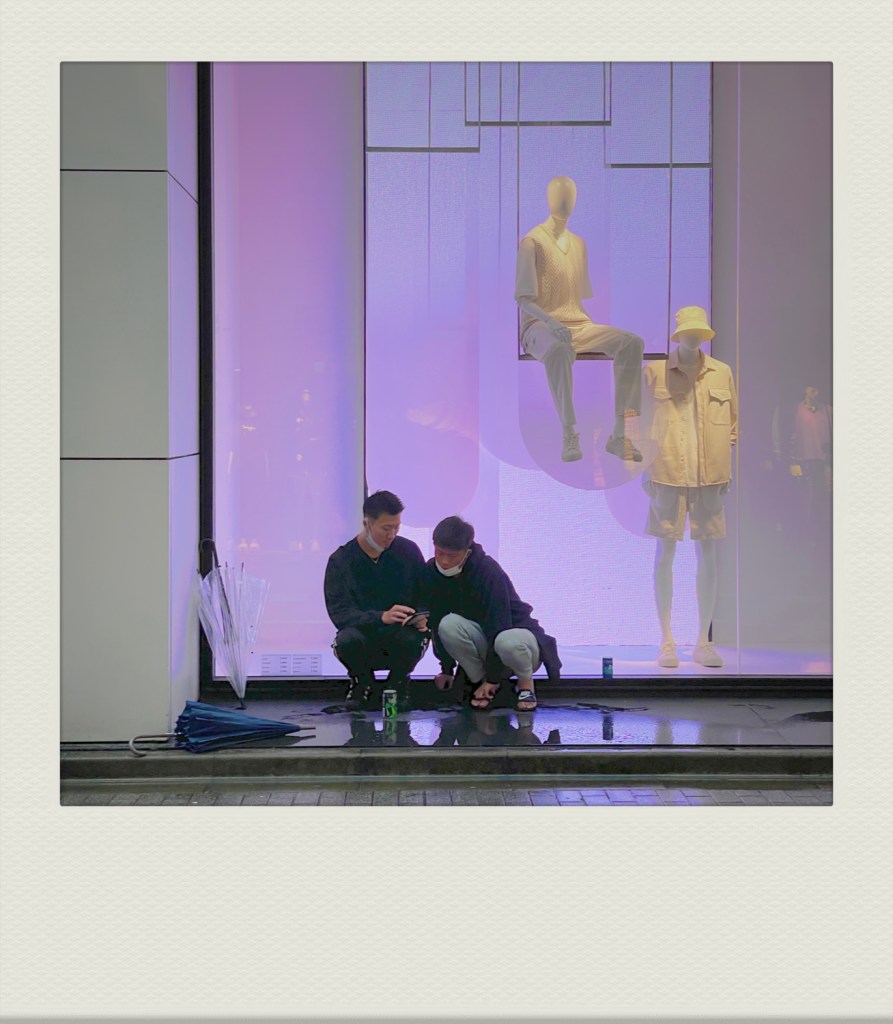

Tokyo. Summer. Covid waves. The Olympics. Obon. This strange brew gives the city a bittersweet flavor. Oppressive summer days are tempered by unexpected tropic-like rain storms or punctuated by days of drizzle. Police foot patrols and mobile holding cells await non-existent law-breakers. Games volunteers, flecks in the landscape in their co-ordinated synthetic uniforms. International Olympic extras hover in hotel lobbies. Non-socially-distanced lines of residents snake around entrances to vaccine centers. Trains and stations are crowded, but not in the way Tokyoites interpret the word. Restaurants close their kitchens early, yet touts on the streets spruik for late-night establishments. Delivery men and Uber Eats cyclists dash about the streets. Repeated announcements about anti-virus precautions and the incessant whirring of cicadas add eerie layers to the city’s soundtrack. Offices are closed, their businesses conducted remotely, but many more are not. Shops of all sizes have closed their doors for good; others have a thriving trade. And everywhere there are hand sanitisers, thermal imaging cameras and thermometers. And masks, and masks, and masks. In August during a resurgent pandemic, the city hosting an Olympiad, Tokyo’s contradictions are ever more heightened, the place seems ever more surreal.

City lights

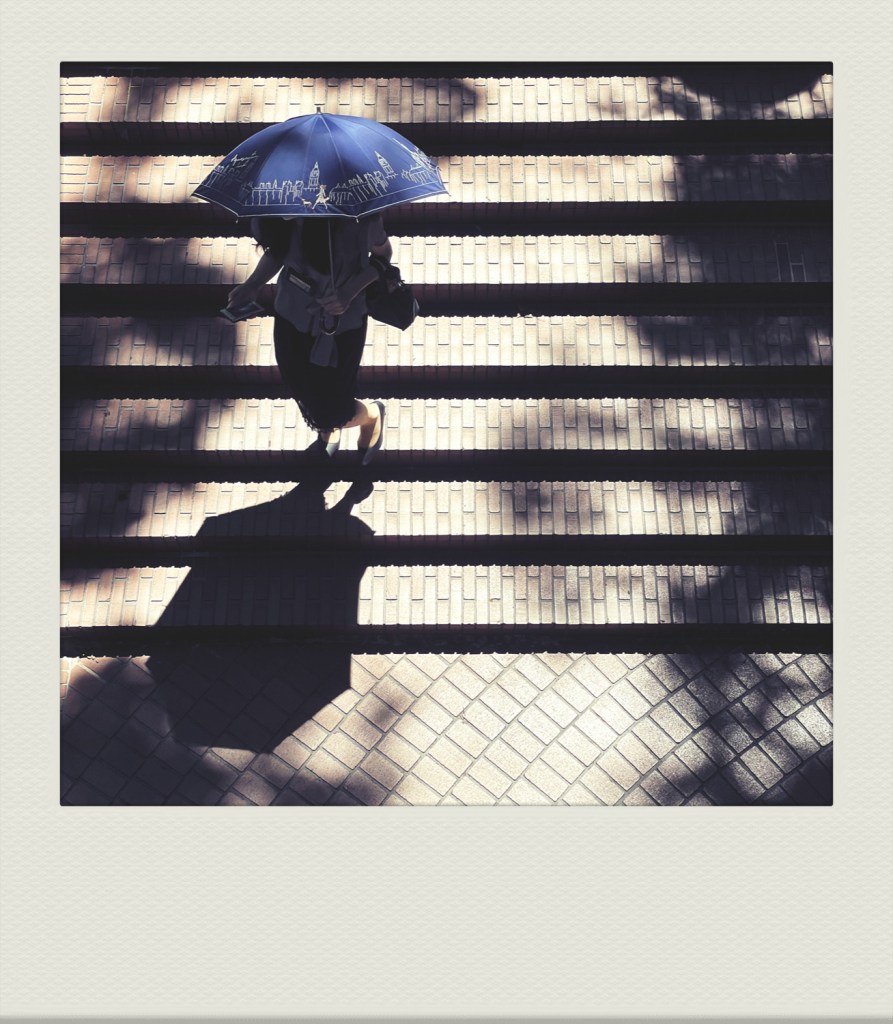

New Umbrellas

In 2014, I published Tokyo Umbrellas as a digital photo book. Though I had previous experience in book and magazine publishing, this was an experiment: my first book of photography. The book was the finishing touch on a project I’d been working on for a couple of years, framing it, giving a defining form and end to the project. In August of that year I put the book out there in PDF form — literally giving it away — and moved on.

In early 2021, while sorting through my files for my print archive, I came across Tokyo Umbrellas and, looking through it, realized it wasn’t all that good; there were good photos, and the basic concept of umbrellas shown used in the rain and sun worked well, but the book was — for want of a better word — bloated. Too many pages, too many images. With the benefit of hindsight and the experience accrued in the interim it was fairly easy to spot flaws in the work.

A benefit of digital books is that making changes is comparatively painless. So I took some time to rework my book.

Tokyo Umbrellas has now been re-edited and redesigned. It is now leaner, comprising a more focused 42 pages that feature 33 images. Less, as it’s often said, is more. This new second edition replaces the original book. Click the video below to flick through its pages. For more information and to view and download the digital book, head to the Tokyo Umbrellas page on this site.

Exodus

A journey of a thousand miles, as it’s long been said, begins with a single step. These days long journeys are, for most people, no more than memories, or dreams. The world, for most of us, has become smaller. I’ve been lucky to be able to travel to just about everywhere my desire took me throughout my life without restriction. I would never have imagined that this would change. But here we are. Borders have been shuttered all around the world. Proverbial thousand mile journeys can be undertaken; actual ones, not so readily these days.

Here in Tokyo, much smaller journeys remain a ritual part of daily life: the never-ending commutes that Tokyoites make on the city’s railway arteries continue. The streams of trains and seemingly countless stations define the dynamism of this city. It can be stimulating; it can be exhausting. The longer you live it, the better you understand the tendency for commuters to doze off on trains. There comes a time when you look forward to escaping it. And so, I’m soon to embark on a journey of almost exactly a thousand miles as I pack up and head to the coastal regions of Okinawa.

Stasis

This is where we are.

Makeshift job interviews conducted on a balcony; supermarket cashiers wrapped in acrylic curtains; patrons separated by plexiglass screens at bars and restaurants; store clerks taking temperature readings at boutique entrances; closed borders; everywhere face masks and bottles of sanitiser. The new normal. A twisted daily lottery of grim statistics. An underlying, persistent fear of infection and anxiety of an uncertain future. A world simulating bleak sci-fi scenarios.

This is where we are.

It’s easy to get swept up in the gloom, to feel stuck, isolated. We connect to the internet for news, for companionship, for shopping, for entertainment. Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos add to their already outrageous fortunes. On our digital screens we see the world is in pain, is breaking: the environment, animal species, human populations, national economies around the globe all suffering. Politics is in a dark place with the rise of fascist tendencies, the death of humanitarianism and ethical imperatives.

This is where we are.

Life feels smaller somehow, the outside world seems rendered with a muted color palette. I wonder if this is the kind of feeling experienced by people living through war. You become fatalistic. Push down the fear and anxiety. Adjust to the new ways of doing things. Lose yourself where you can: in work, in activism, in hobbies, in passion projects, in creative pursuits, in destructive pursuits, in mindless pursuits. You grit your teeth and make the best of a bad situation; keep calm and carry on, as it were.

Traces

A stroll down Hachiman Dori, past Piotr Kowalski’s vibrant Sunflower sculpture and into the neighboring Tenoha Daikanyama courtyard, to relax with a coffee among leafy trees and shrubs. A good coffee shop is an elusive thing, a perfect blend of well-made coffee and atmosphere.

This corner cafe fit the bill nicely, but just like that, it’s gone — together with the courtyard, restaurant, gift shop and co-working office space that formed the Tenoha complex. The entire site has disappeared, bulldozed to the ground, like so many places in Tokyo, to make way for a newer, bigger, more profitable construction.

At times when I look back through my archives, look through photos taken in Tokyo over the years, I often see places that I captured, stores and restaurants I frequented, and realize they no longer exist. Of these places there are no traces left. In time even their memories have faded. In the end there are only photographs. The places below that I’ve recently documented do still exist, but I wonder for how long?

Daido ongoing

Daido Moriyama, 森山 大道, is the ultimate street photographer. He’s been walking the streets of Tokyo with one compact camera or another in his hand for going on sixty years, snapping fragments of the city and its inhabitants from his singular perspective, both capturing and helping to shape the city’s distinctive character.

A nicely curated exhibiton of Moriyama’s mostly recent work is currently showing at the TOP Museum in Ebisu. The images in Moriyama Daido’s Tokyo: ongoing are spread over three rooms. Greeting the visitor in the first space is a large gelatin silver print of the photographer’s iconic Stray Dog, Misawa, placed by a Warhol-esque silk-screened mosaic of cloned lips, half monochrome, half in color, covering one wall like pop art wallpaper. Opposite is a series of striking oversized inky black, high contrast silk-screened portraits, grainy, some resembling pointilist artworks. The larger adjoining central space contains the bulk of the works and also groups images into tiled mosaics, three photos high, monochrome on one side of the room, color on the other. Close up images of hair, legs and signs are mixed in with frames of alleys, pedestrian crossings and other streetscapes. Here and there is the occasional portrait or reflected self-portrait. The effect of juxtaposing so many images is to give a sense of the city’s at times overwhelming kinetic energy, especially in the color photos, many of them quite lurid. A pair of square glass-topped tables frame monochrome collages, formed by layering and overlapping prints at seemingly random angles, hiding and revealing elements of each. Given the visual complexity on show in this space, there’s plenty to take in, so a small third space serves as a kind of decompression chamber. It’s cloistered, hidden by heavy curtains, and features a few black and white frames from Moriyama’s abstract mesh tights series, each incandescent with the backlighting of the digital screen it is displayed on. The atmosphere here is intimate, contemplative, personal, and despite the eroticism of the photos, is more church confessional than peep show.

A good exhibition is always invigorating. In photography, as in all creative pursuits, it’s sometimes hard to maintain momentum. Moriyama himself bid farewell to photography in 1972 with his book shashin yo sayonara. His hiatus was fortunately short lived and he has since applied himself to his art: Moriyama has one hundred and fifty or so books to his name, has been exhibited dozens of times around the world and has received a handful of prestigious photography awards — and he’s still out on the streets with his camera almost every day. The 81 year old photographer is an inspiration.

Note: photography is not allowed in this exhibition; the photo above was taken in 2016 at another Moriyama exhibition in Tokyo.

Rainy day blues

Tokyo, where the rainy season is fast approaching, where misty grey days will damp the air and violent deluges will blot out darkened skies. Just now it seems a bleak metaphor: the heavens crying for a world out of whack, weeping for Britain and Brazil and the idea that was America.

Tokyo, where the restrictions of lockdown lite have been officially lifted, where the department stores have raised their shutters, high school students have once again donned their uniforms and life on the sidewalks has become more animated. And yet…

Tokyo, where in a reverie I recall a hypnotic film I saw many years ago. Almost forty years old, Koyaanisqatsi seems made for our times. Pairing time-lapse and slow motion visual techniques with the pulsating music of Philip Glass, it attempts to convey how we’ve created a world out of balance; the Frankenstein story writ large.

Still lifes

If you fall down the various rabbit holes of online photography forums, you‘re likely to get ulcers or develop anger management issues. Many forum contributors have very strict rules and definitions about the rights and wrongs of photography and they type out their resolute assertions in the endlessly scrollable online debates. But the thing is, aside from photojournalism and other documentary practices that strive to present truth, there are no rules in photography. It’s an art, a medium, a process whose countless practitioners show that it can be explored with all manner of tools and pushed any which way. And if you work at it, you may just end up with something worthwhile.

Ok, but my photography doesn’t always fit into neat, coherent projects, so maybe I need to roll freeform around this world, unfettered, able to photograph whatever and whenever: the sky, my feet, the coffee in my cup, the flowers I just noticed, my friends and lovers, and, because it’s all my life, surely it will make sense? Perhaps. Sometimes that works, sometimes it’s indulgent, but really it’s your choice, because you are also free to not make ‘sense’.

…

And hopefully I will carry on, and develop it, because it is worthwhile. Carry on because it matters when other things don’t seem to matter so much: the money job, the editorial assignment, the fashion shoot. Then one day it will be complete enough to believe it is finished. Made. Existing. Done. And in its own way: a contribution, and all that effort and frustration and time and money will fall away. It was worth it, because it is something real, that didn’t exist before you made it exist: a sentient work of art and power and sensitivity, that speaks of this world and your fellow human beings place within it. Isn’t that beautiful?

British photographer Paul Graham penned these thoughts for the graduating students of the Yale (MFA) Photography program in 2009, in a brief but illuminating essay, Photography is Easy, Photography is Difficult.

These pictures: more digital polaroid explorations; local street signage and other found graphic elements framed to create still life compositions; character studies of a neighborhood.

In the weeks since, my explorations have found a focus and taken shape and I’ve been able to develop a photographic series, one I expect will be organic and episodic in nature as it evolves.

Views from the ‘hood

And the one nice thing about photography is it teaches you to look.

So said Saul Leiter In Tomas Leach’s 2012 film on the photographer In No Great Hurry. He also said in interview that he thought that mysterious things happen in familiar places, that there was no need to run to the other end of the world to create his art.

Saul Leiter lived in the same apartment building on 10th Street in New York’s Lower East Side — later to become the East Village — for some sixty years, and true to his word, much of his extensive body of work was created within walking distance of his apartment.

I haven’t lived anyplace anywhere near that long, yet it’s surprisingly quick and easy to turn a blind eye to our most familiar surroundings, to become desensitized to our immediate environment, to see through things. Losing mobility, even in Tokyo’s lockdown lite situation, for all its inconveniences has a way of restoring one’s vision. Everything old may not be new again, but one develops a new appreciation of the old neighborhood streets, sees the effect of changing weather on its vistas, notices picturesque elements in the landscape.

These images resulted from a number of recent walks around the neighborhood, visiting the supermarket, stretching my limbs and — despite being masked up and just a little bit anxious — getting some air and respite from being cooped up inside, and with my camera, looking at the neighborhood with fresh eyes.