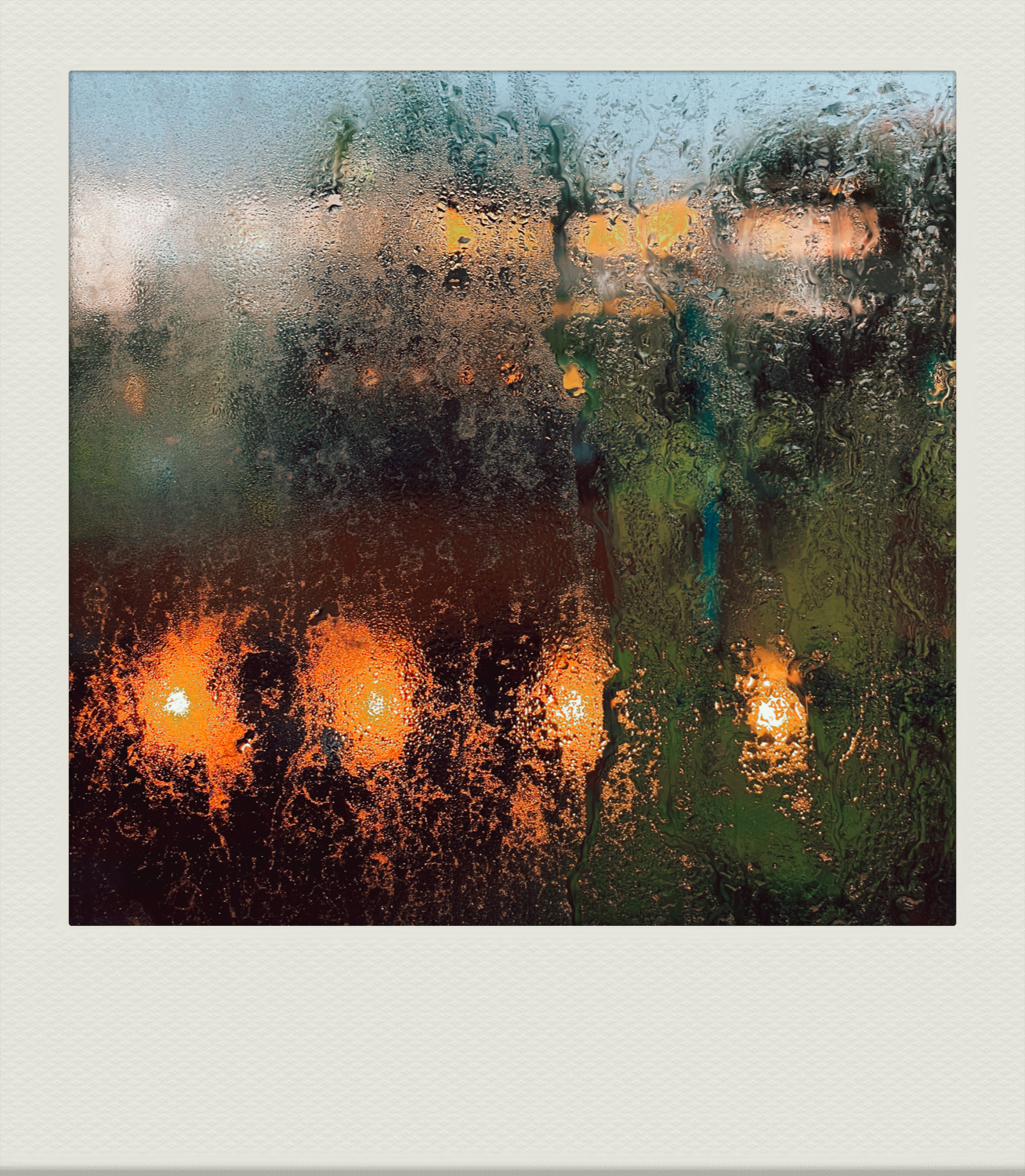

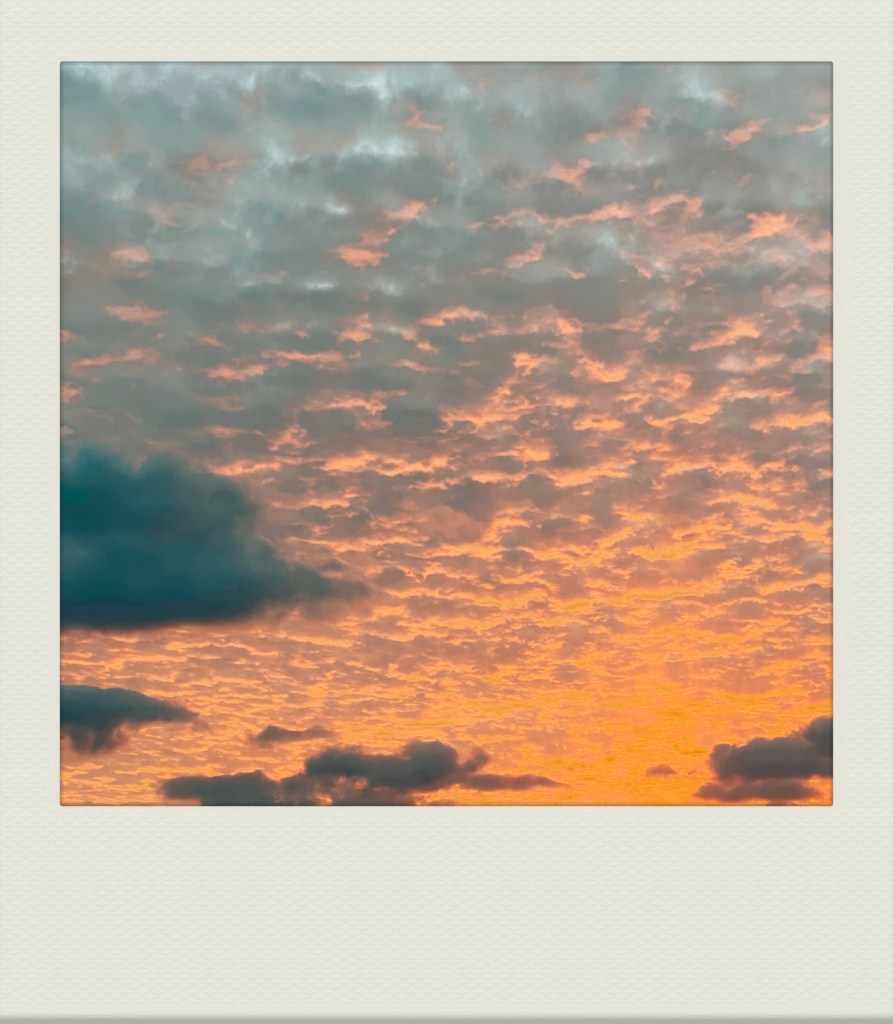

Look at the breadth of this city, the height of its buildings, the speed of its trains and the wealth of its people. This city that was once ash, that was then wood, fields of ash and forests of wood, that is now concrete, steel and glass, mile upon mile of concrete, steel and glass.

British writer David Peace returns to Tokyo with his latest publication, the final volume of a trilogy of historical crime novels set in post-war Tokyo that I am very much looking forward to reading. In preparation, I’ve begun re-reading the two earlier novels. It’s been a long time between drinks, as they say. The first book, Toyko Year Zero was published in 2007. Occupied City followed in 2009. Fictionalized accounts of actual murders that were committed in Japan’s Shōwa era, the two books — stylistically and formally adventurous and steeped in dark hallucinatory atmospheres — focus on Tokyo in the years immediately after the country’s surrender and occupation by the American military: 1946 and 1948 respectively. The final book in the trilogy, Tokyo Redux, concerns itself with a murder committed in 1949, but also visits the city in 1964, the apex year of the Tokyo Olympics, and 1988, during the dying days of the Emperor Hirohito and the Shōwa era.

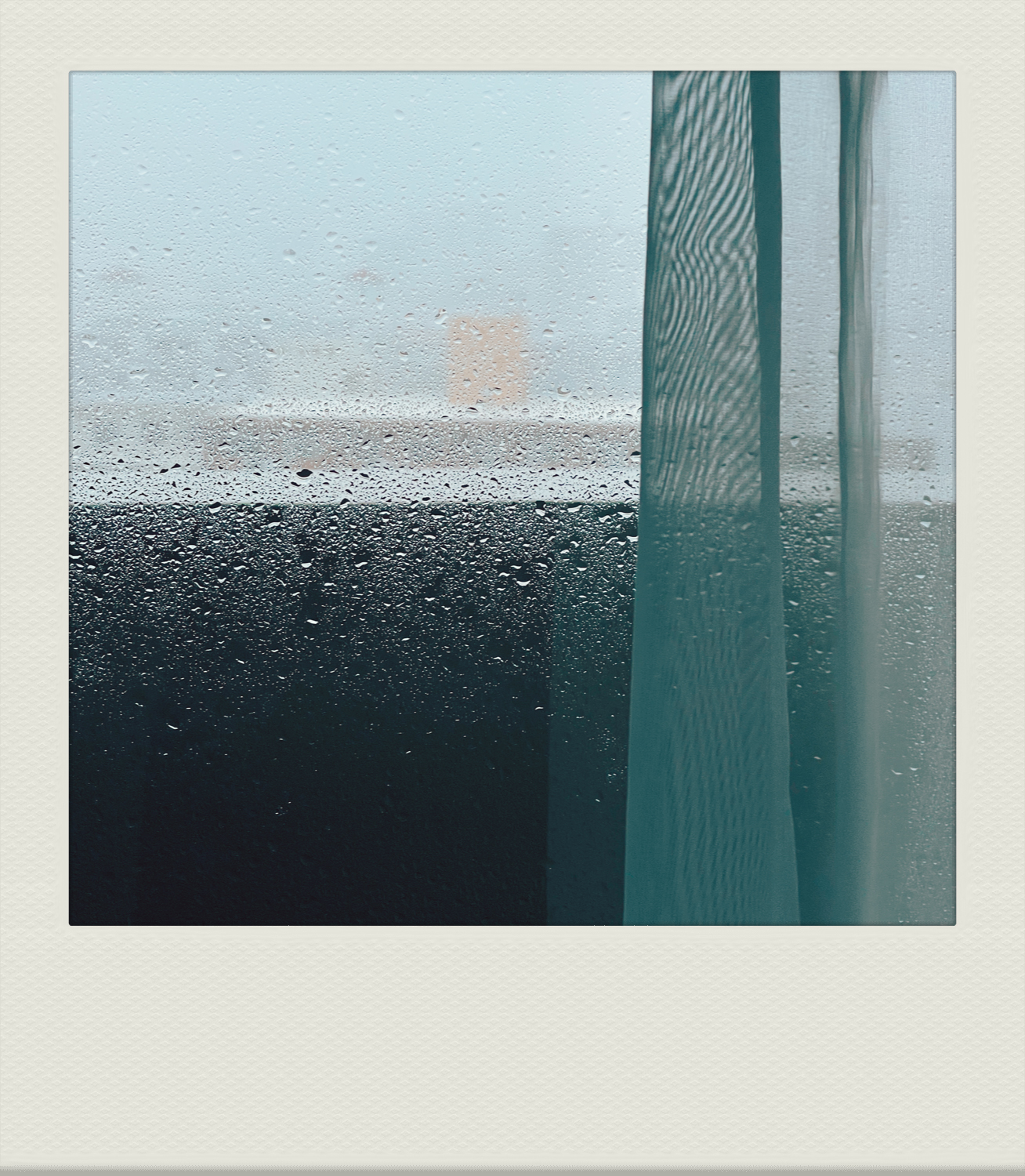

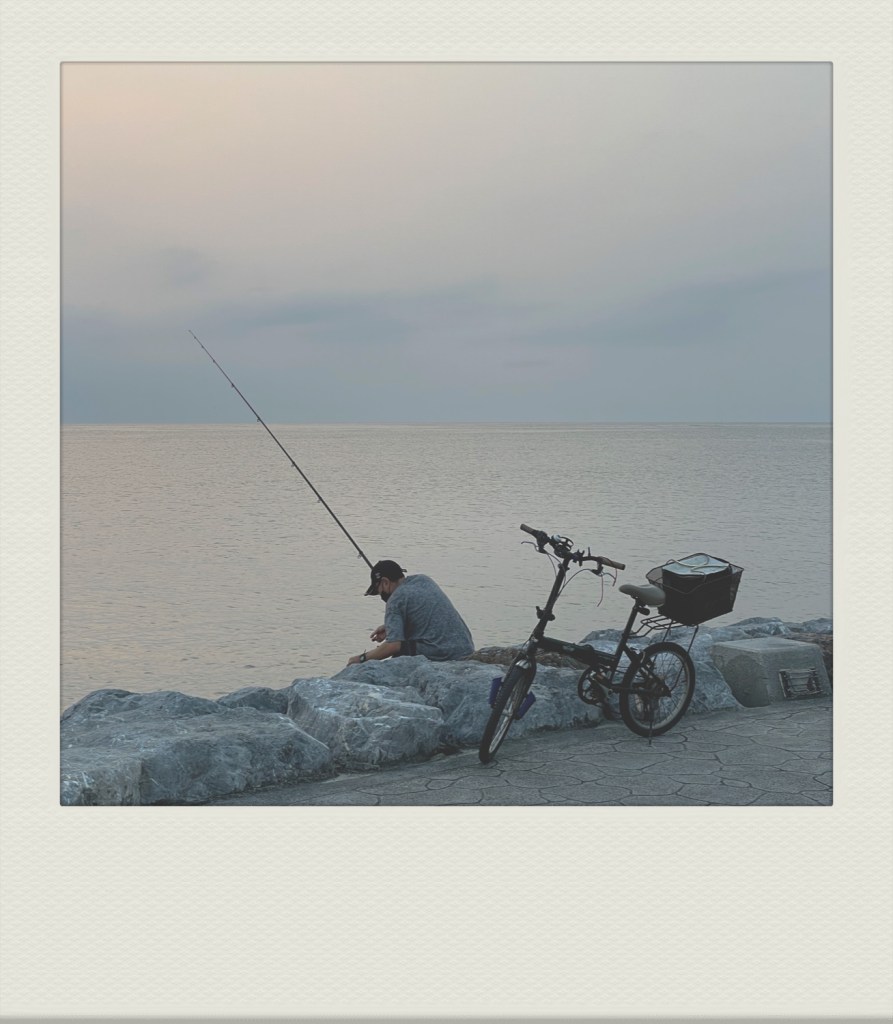

Obviously the bleak city envisioned in Peace’s trilogy is far removed from the Tokyo I know, but Tokyo Redux appeared just weeks before my own impending return to the city, to a place that continues to grapple with the demons of a pandemic that refuses to die and whose hapless leaders struggle to balance economic and public imperatives. In this atmosphere, the book should be a stimulating companion as I reacclimatize to life in Tokyo.